At a key UN summit in Nairobi this month, governments will discuss the path towards the first global treaty to tackle plastic pollution. But with multiple proposals on the table, the scope and ambition of such a treaty hang in the balance.

The United Nations Environment Assembly, which is scheduled for 28 February-2 March in the Kenyan capital, could result in a mandate for an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to work out a legally binding agreement obliging countries to eliminate plastic pollution leakage – especially into oceans – through national targets and plans for plastic reduction, recycling and management.

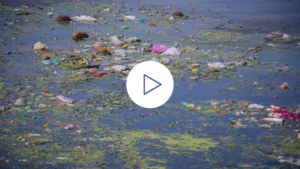

There’s an incomprehensible amount of plastic in the ocean. Estimates put the known total at up to 51 trillion plastic fragments in surface waters alone. Marine plastic pollution harms animals, which ingest or become entangled in it, while the risks to humans who eat seafood contaminated with plastic toxins are still unknown. Much of the plastic waste entering the sea comes from rivers.

But plastic pollution is not restricted to water. Plastics have been detected in every corner of the Earth, from the Arctic to the top of Everest. What’s more, plastic is a major driver of climate change. If the whole plastics lifecycle were a country, it would be the fifth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world.

While per capita production of plastic waste is lower in South Asia than most other regions, overall production of solid waste is projected to double by 2050. Meanwhile huge quantities of plastic waste in Southeast Asia come from developed nations, who export it to developing countries to recycle or dispose of. Following China’s ban on waste imports in 2018, imports of plastic to Thailand increased by 1,000% between 2018 and 2020. While India and Bangladesh have also banned imports of plastic waste, illegal imports continue to create environmental problems.

With plastic pollution in the world’s oceans and waterbodies projected to double by 2030, pressure has been building to find a global solution to limit the production of the material in the first place – which only a global deal can achieve.

What might a global treaty on plastic pollution look like?

Existing global treaties cover elements of the plastic problem: the Basel Convention regulates trade in waste, including plastic; the International Maritime Organization is responsible for marine plastic litter from ships; while the Stockholm Convention protects humans against harm from plastic products. However, none represent a holistic tool to tackle plastic pollution at the global level. Unlike climate change and biodiversity loss, there is currently no international framework to address plastic pollution, despite growing recognition that it, too, could pose a ‘planetary boundary threat’.

Momentum has been building ahead of this month’s UN Environment Assembly talks (known as UNEA-5.2), with 154 states already supporting talks on a new global agreement. In January, more than 70 consumer brands including Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Unilever and IKEA issued a joint statement setting out plans for reducing plastic production and use. Significantly, the US, the world’s largest producer of plastic waste, announced late last year that it would participate in talks.

In order for negotiations over a global treaty on plastic pollution to begin, a resolution which sets the scope and mandate for these negotiations must first be adopted at the UNEA-5.2.

Three such resolutions have been tabled which would set out the scope of negotiations over a future global agreement. Two of these call for a legally binding framework on plastics which would be the first of its kind. But the differences between the two are significant.

One resolution, tabled by Rwanda and Peru with 54 co-sponsors including Pakistan, the Philippines, South Korea, Timor-Leste and the EU, is considered the most ambitious. It proposes an ‘open mandate’ for a negotiating committee, meaning negotiators could work on a range of issues relevant to plastic pollution as discussions progress. It suggests a ‘full life cycle’ approach to plastics, tackling plastic production as well as waste management, and is also worded to address plastic pollution in any environment, not just marine litter.

A second resolution from Japan, and co-sponsored by Antigua and Barbuda, Cambodia, Palau and Sri Lanka, is more limited in scope. The resolution specifically addresses “marine plastic pollution”; is focused on management of plastic waste (rather than production); and proposes a closed mandate, which would mean negotiators could not address other aspects of plastic pollution when working towards an agreement.

India entered discussions at the 11th hour with an alternative resolution on single-use plastics, published on 31 January. Unlike the other proposals, India’s document focuses on a voluntary framework – with an emphasis on single-use plastics – rather than a mandate for the creation of a legally binding global agreement.

Commenting on India’s proposal, Christina Dixon, deputy ocean campaign lead at the Environmental Investigation Agency, said: “While it has some useful suggestions, it ultimately proposes the continuation of the current state of play, with some modifications, and does not recognise the need for a legally binding approach. This is contrary to broad global support for the need for something legally binding at the global level, and acknowledgement that voluntary action is insufficient.”

We are on the precipice of securing a potentially world-changing global agreement on plastic pollution and it is essential that governments remain ambitiousChristina Dixon, Environmental Investigation Agency

All three published resolutions are being discussed prior to UNEA-5.2, at meetings of the Committee of Permanent Representatives. Several UN member states have asked that the two original proposals be merged in advance of the main summit.

“Japan has already started dialogue with Norway [a co-sponsor of the first proposal],” Shahriar Hossain, secretary general of the Bangladesh-based non-profit Environment and Social Development Organization (ESDO), told The Third Pole. “I believe that nobody is interested in going for a vote, so they will come up with some compromise plan.”

In a statement with the G77 on 3 February, China stated its support for starting negotiations on plastic pollution, calling for “ambitious goals and equally ambitious means of implementation”, and pledging to “engage actively and constructively in the negotiation of the different tabled resolutions”.

Civil society urges ambition and attention on finance

Hossain told The Third Pole that his organisation, which is a member of the NGO coalition Break Free From Plastic, is urging governments to support the broader proposal from Rwanda and Peru. “We believe that the plastic treaty should cover the whole life cycle of plastics. It is not just marine litter, it is also land-based pollution. The process of plastic pollution starts when the raw materials are produced. This is a petroleum-based product – and it doesn’t end with waste dumping.”

Commenting on what would be a disappointing income, Hossain added that “most developed nations have vested interest groups. There might be a focus on marine litter, and that would be most disappointing, if they move in that direction [excluding the life cycle of plastics and terrestrial plastics issues].”

Dixon emphasised the need to avoid such a narrow approach. “We are on the precipice of securing a potentially world-changing global agreement on plastic pollution and it is essential that governments remain ambitious on its scope, equipping it with a mandate to look at plastic pollution across its lifecycle and in all environmental compartments,” she said.

Andrew Norton, director at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), said that reducing reliance on plastics was essential to achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

“A number of countries, often low-income and with weak governance structures, have ended up as the processors, and frequently the dumping grounds, for plastics from richer nations. Major investment and support will be needed to find viable alternative models for dealing with plastic that properly incentivise more sustainable and just practices in future,” he said.