Bangladesh has recently built the largest human waste management plant in Cox’s Bazar, which is now home to almost a million Rohingya refugees. This industrial scale mega plant, claimed by UNHCR and Oxfam to be ‘the largest among the refugee camps in the world’, can process the waste generated by more than 100,000 people every day.

Funded by the UNHCR, Oxfam engineers built this mega plant consisting of two lagoons and a polishing pond in Kutupalong Refugee Camp that houses more than 550,000 Rohingya refugees. The authorities opened the plant in February this year. Oxfam engineers said it took seven months for them to build this massive system specially designed for the steep, hilly terrain and to have the cheapest possible operation and maintenance cost.

Cox’s Bazar is now home to more than a million Rohingya refugees. More than 750,000 of the Rohingya came to Bangladesh in 2017 to escape persecution and violence by the Myanmar’s military in northern Rakhine state. They live across a number of different refugee camps.

See: Rohingyas caught in vice grip of identity politics and land grabs

The challenge of human waste

Given the scale and speed of the refugee influx, the need for clean and safe sanitation facilities has been a constant challenge. Sanitation facilities in the Rohingya camps were mostly created as stop-gap measures, which would have been enough for temporary residents. Over time waste management has become a serious concern with high levels of diarrhoea, respiratory infections and skin diseases like scabies. These are all linked to poor sanitation.

In 2018 there were more than 200,000 cases of acute diarrhoea reported in the Cox’s Bazar camps, according to the WHO and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

Salahuddin Ahmmed, a public health engineer at Oxfam said, “It is estimated that a person produces four hundred grams of waste per day.” With a million refugees in camps, the human waste generated every 24 hours is staggering. In order to address the pressing need for waste management, the government of Bangladesh, Oxfam and UNHCR partnered together to build this mega structure.

Although this technology has been around for a while, the creation of this large waste management structure may help in dealing with other such situations. The most common method of waste disposal during any emergency or temporary situation is to use tankers to suck out the sewage from latrines and take it away. But around 85% of the world’s refugees are in developing countries, often lacking adequate sewage systems to deal with the extra waste, making this difficult. Another advantage of on-site treatment of the waste is that reduces the risk that waste will end up being dumped in a nearby field or polluting a local water body.

The technology

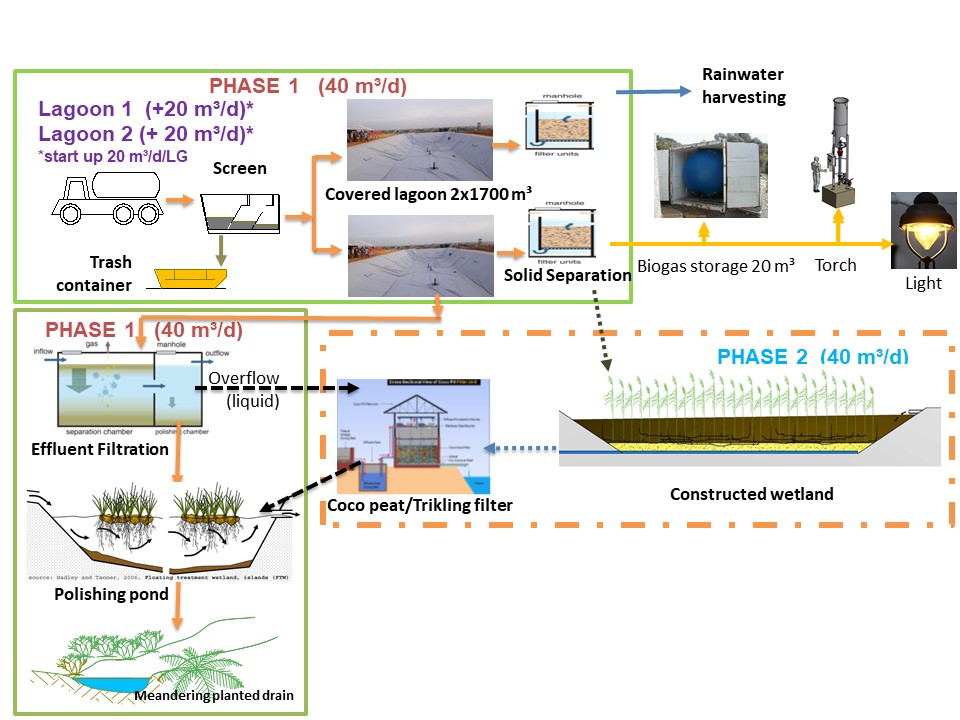

The newly built faecal sludge management plant is made up of treatment ponds and wetlands. It ensures the safety of both people and the environment, according to a press note by Oxfam. The plant has multiple treatment stages to prevent contamination of local water sources and a high-density polyethylene liner and covered anaerobic unit to stop unpleasant odours escaping.

The lagoons in question, he said, “can take approximately 40,000 litres of sludge per day.” This would lead to the treatment of waste generated by more than 100,000 people.

The liquid sludge is drained into a pond at the end of the lagoon which is known as the ‘polishing pond’. During it journey to the pond, the liquid passes through a filter consisting of coconut fibre, gravel, sand and other natural particles that helps remove solid or biodegradable components. The liquid that passes through is then decontaminated before being released.

A separate procedure is needed to deal with the settled solid waste, which is pumped out of the lagoon and into a planted de-watering bed. “The remaining solid waste stays in the drying bed and naturally degrades with the help of plants and sunlight.” The bed planned in the area will have a ten year lifetime. The plant itself has a 20 year life cycle, and takes only three people to run. The Oxfam release says that it has been, “designed by a German organisation called BORDA – specialists in sanitation systems in developing countries.”

A broad application of technology

During the inauguration of the building, Bangladesh’s State Minister for Disaster Management and Relief, Enamur Rahman said he hopes to have similar treatment plants in other Rohingya refugee camps.

Bangladesh has been trying to convince the international community to put pressure on Myanmar to start the promised ‘repatriation’ process. Both the governments have signed an MoU to start the repatriation of Rohingya people. There has been effort from the Bangladesh side to facilitate the repatriation last year. But no one from the Rohingya community agreed to go back to their country as they still are not convinced about the guarantee of safety in Myanmar.

The aid agencies are calling for more aid and resources to improve conditions of the refugees now living in Bangladesh beyond the basics. They also urged both the governments to ensure that the repatriation is safe and voluntary.

It is not still clear when repatriation will happen. The recent attempt of a repatriation exercise failed. Now many people have started feeling that the refugees will live in Bangladesh for indefinite period of time.

If so, more such waste management plants will be required to address the sanitation and hygiene in refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. At least it will help ease the tensions between the refuges and the local population, which have been aggravated by the environmental destruction of hundreds of thousands of people relying on wood from forests for their necessities, and having nowhere to dispense their waste.

See: Barren hills bring Rohingya refugees and Bangladeshis into conflict

While the treatment plants have an obvious downside – the lagoons for natural treatment require a great deal of land area in a country with chronic land shortage – the technology may be useful for Bangladesh beyond just refugee camps. There is no cement structure needed, and no water is used in the process. Bangladesh is dealing with a large challenge when it comes to dealing with human waste, and the government has already asked Oxfam and other agencies to see if this technology can be adapted to urban areas for general use. The local communities around the refugee camps may also see such waste treatment plants coming up, and so, in a way, Bangladeshis as a whole may benefit from taking care of the refugees.

![<p>One of the lagoons where the waste will be treated [image by: Maruf Hasan]</p>](https://www.thethirdpole.net/content/uploads/2019/04/FSM-3-1-300x169.jpg)